David Rosenhan walked into the admissions office of a psychiatric hospital on February 6, 1969, and told the staff that he was hearing voices. He said they sounded unclear, but they seemed to be saying three words: empty, hollow, thud.

That was it. That was all he gave them.

No outbursts. No erratic behavior. No tragic backstory of unraveling mental stability. Just a single, vague symptom.

He was admitted immediately.

Rosenhan was a professor of psychology at Stanford, and he wasn’t actually sick. Neither were the seven other people who followed him into psychiatric hospitals across the country. They were all volunteers in an audacious social experiment—an attempt to answer a simple but unsettling question: How good are doctors at telling the difference between the sane and the insane?

The answer was not encouraging.

How Psychiatric Labels Stick Forever

Rosenhan and his “pseudopatients” went to twelve different hospitals: big, prestigious institutions and small, underfunded facilities. Some were well-regarded, some were not. It didn’t matter. Each of them was diagnosed with a severe mental disorder, mostly schizophrenia. Once inside, they behaved completely normally. Polite, cooperative, and stable. But instead of being discharged, they found themselves trapped.

Doctors observed them carefully, meticulously documenting their supposed pathologies. One patient was seen taking notes on the ward. Something you or I might do if we found ourselves locked in a psychiatric hospital as part of a scientific study. This note taking received a diagnosis: pathological.

Another patient was spotted pacing the hallways because, as he later said, he was bored. The staff interpreted it as nervous agitation, a classic sign of schizophrenia.

Even polite attempts at conversation could end up reinforcing a diagnosis. One pseudopatient asked a nurse, “When am I eligible for discharge?” and got no real answer. Instead, the staff added to the patient’s chart that they had “anxiety about discharge.”

The shortest hospital stay was seven days. The longest? Fifty-two.

When Hospitals Falsely Identified Real Patients as Fakes

When Rosenhan finally published his study in Science in 1973, the psychiatric community was furious.

One hospital, a prestigious research institution, angrily challenged him: That would never happen here. We’d spot a fake in an instant.

He accepted their dare. Over the next three months, the hospital identified forty-one patients they were certain had been planted by Rosenhan.

Except Rosenhan hadn’t sent anyone.

Every single person they flagged as a fraud was a real patient.

Psychiatry had failed twice: first, by diagnosing sane people as insane. And then again, by diagnosing insane people as sane.

The Journalist Misdiagnosed with Mental Illness

Photo: Susannah Cahalan

Susannah Cahalan was twenty-four years old when her life began to unravel. She started hearing voices, became convinced her boyfriend was cheating, and swung wildly between elation and despair.

As her paranoia grew, she suffered severe seizures and terrifying hallucinations that were so severe she ended up in the hospital. One doctor diagnosed her with schizoaffective disorder, prescribed antipsychotics, and warned that her future looked grim.

But something didn’t add up. A neurologist, Dr. Souhel Najjar, suspected a hidden medical issue and asked Cahalan to draw a simple clock. She packed the numbers onto one side of the circle, an alarming sign that part of her brain wasn’t functioning properly.

This led to deeper tests which revealed anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis, a rare autoimmune disease in which the body attacks the brain, mimicking severe psychiatric disorders. Once doctors realized the true cause, they treated Cahalan with immunotherapy—high-dose steroids, IV immunoglobulin, and plasma exchange—and she slowly emerged from the nightmare.

Had no one noticed those clues, she might have spent years under a psychiatric misdiagnosis. Instead, pinpointing the physical root of her condition not only saved her health but also proved she wasn’t “crazy” after all.

Why Mental Health Misdiagnosis Keeps Happening

Rosenhan’s study was supposed to be a wake-up call. But Cahalan’s story proves that we haven’t learned its lesson.

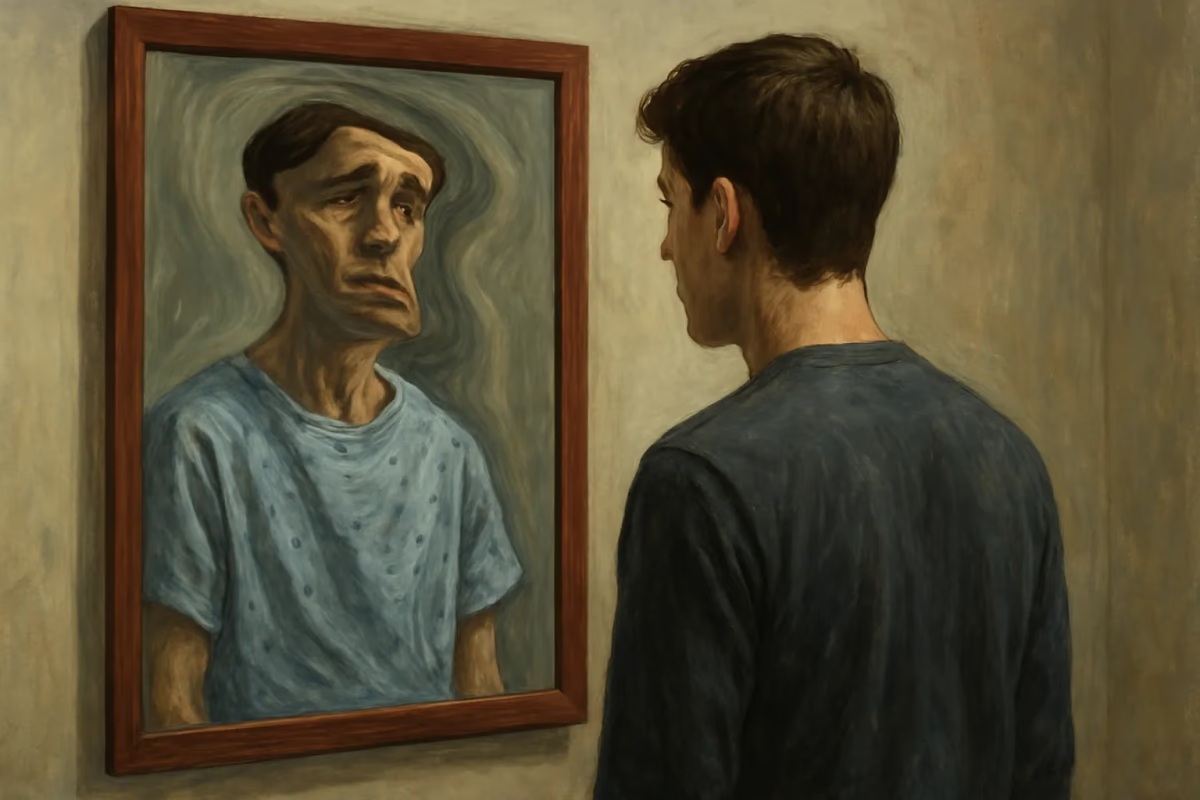

We like to think of psychiatric diagnosis as scientific and precise. But it isn’t. It’s a guessing game. It’s an interpretation of behavior based on the context in which it’s seen. Once a person has been labeled mentally ill, crazy, or schizophrenic, everything they do is filtered through that lens.

A person taking notes in a psychiatric ward? Paranoid.

A woman crying after an argument? Hysterical.

A patient who seems unresponsive and vacant? Catatonic.

What if they’re just bored? Or frustrated? Or exhausted?

What if they’re actually suffering from an autoimmune disease, like Cahalan? Or a metabolic disorder? Or lead poisoning?

In one retrospective analysis at the Johns Hopkins Early Psychosis Intervention Clinic, about half of the patients referred with a schizophrenia diagnosis turned out to have something else entirely upon further evaluation.

And what about the people who never even step into a hospital? The employee who gets labeled as “difficult” instead of being diagnosed with ADHD. The teenager seen as a “troublemaker” instead of someone struggling with undiagnosed autism. The girl who gets dismissed as “moody” when she’s actually suffering from bipolar disorder.

The psychiatric system doesn’t just mislabel people inside hospitals. It mislabels people everywhere.

What We Still Haven’t Learned from Rosenhan’s Experiment

Rosenhan’s experiment is more than fifty years old. Cahalan’s story is more than a decade old. But the lesson is timeless:

We are too quick to categorize people.

And once we’ve put them in a category, we stop seeing them. We see the label instead.

The next time you meet someone who seems off, resist the urge to diagnose them. Maybe they’re not crazy. Maybe they’re not difficult. Maybe they’re not lazy.

Maybe they’re just a person, trying to be understood.