It’s December 31, 1999. At the White House Y2K command center, John Koskinen, America’s designated Y2K czar, stares at monitors as midnight creeps across time zones. Officials from government agencies are hovered around him, waiting for a digital apocalypse they’ve spent billions trying to prevent.

Are banks collapsing? Nope.

Any planes falling? Nada.

Is the power grid failing? Negative.

Four days later, Koskinen stands before reporters: “We can safely say what has been referred to as the Y2K bug has been squashed.” The most hyped tech disaster in history was a complete dud.

But was it ever real? Twenty-five years later, we still argue whether Y2K was humanity’s greatest tech save or an embarrassing mass delusion. The truth? It was a mix of both.

What Was the Y2K Bug and Why Did Everyone Panic?

Photo: Y2K Sticker / Best Buy

The Y2K “bug” is a bit comical now. The story goes like this: Back in the day, when computer memory was scarce and absurdly expensive, programmers had to be ruthless about saving space. So instead of writing out the full four-digit year, they cut corners: “85” meant 1985, “99” meant 1999. It seemed harmless. Efficient, even.

Then someone asked: What happens when “99” rolls over to “00”?

As it turns out, nobody planned that far ahead. Computers, for all their supposed brilliance, might take “00” to mean 1900 instead of 2000. Which, depending on the system, could mean anything from “your credit card doesn’t exist yet” to “congratulations, all your data just imploded.”

A simple formatting shortcut threatened to unravel modern society.

And the bug wasn’t just lurking in some forgotten financial mainframe. It was everywhere. Buried in the code of elevators, traffic lights, power plants, hospital equipment, millions of embedded chips that nobody had thought to check. A Senate report didn’t hedge, warning bluntly: “Failure of some parts of the electric power system are likely.” Not possible, not a worst-case scenario if things go sideways, but likely.

What started as a minor IT concern had grown into a full-blown crisis. The Gartner Group estimated the global price tag for fixing it could hit $600 billion. Congress created a special Y2K committee. President Bill Clinton appointed Koskinen as the U.S. “Y2K czar.” For a date glitch.

Mass Hysteria in 1999 Over Y2K Nuclear War Scenarios

By 1999, the world was bracing for impact.

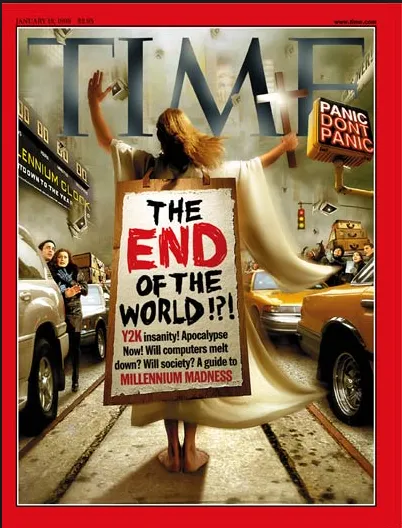

Edward Yardeni, an economist for Deutsche Bank, placed the odds of a global recession at 70%. A Gallup poll found that 20% of Americans had turned into basement preppers, hoarding canned beans and bottled water. Meanwhile, TIME Magazine went full tabloid with THE END OF THE WORLD!?? on its cover. (Two question marks and an exclamation point—real journalistic restraint.)

Photo: Y2K TIME Magazine Cover

But maybe TIME had a point. The U.S. government acted like it did. The Federal Reserve stashed away $50 billion in cash, bracing for bank runs. The Pentagon dumped about $4 billion into updating military systems. And the State Department warned Americans to steer clear of countries they feared weren’t prepared.

There was also the minor issue of accidental nuclear war.

Behind closed doors, the nightmare scenario wasn’t bank runs or busted vending machines; it was nuclear war by accident.

Russia’s missile warning systems were relics. If those aging systems tripped over the date change, they could mistake routine blips for an incoming American strike. And if that went wrong? Well, let’s just say the new millennium would have kicked off with a much brighter flash than fireworks.

The risk was real enough that the U.S. and Russia took the unprecedented step of setting up a joint monitoring center. Russian and American officers sat side by side, staring at the same screens, making sure a technical glitch didn’t get mistaken for Armageddon.

How the World Spent $300 Billion Fixing Y2K

The scale of the global response was unprecedented, with worldwide estimates around $308 billion.

Corporations freaked out. Banks ran massive simulations to see if their systems would self-destruct. Wall Street literally fast-forwarded its clocks in a “Streetwide” test. Utility companies rehearsed worst-case scenarios like they were prepping for the Super Bowl of electrical failure.

Programmers who knew COBOL (a “legacy” coding language) suddenly became indispensable. Businesses weren’t just patching their software; many used the crisis as cover to finally upgrade systems they’d neglected for years.

By the final weeks of December, the U.S. government announced confidently that 99% of critical systems were fixed. Banks, airlines, and other major industries gave similar reassurances. Still, no one fully trusted that smaller businesses or foreign countries had done enough.

As New Year’s Eve approached, tech workers everywhere prepared to camp at the office. Reporters worldwide stood by, cameras pointed less at celebrations and more at screens and servers, anxiously waiting to see if everything held together.

What Really Happened When Y2K Hit?

Photo: Times Square, January 1, 2000 / Paul Mannix

Then came January 1, 2000.

And… nothing.

Well, almost nothing.

Pakistan’s stock exchange suffered a few glitches, requiring traders to manually record their transactions. A radiation monitoring computer at a nuclear plant in Japan threw an error, but technicians quickly resolved it. And some websites welcomed users to the year 19100.

But aside from minor issues here and there, the apocalypse that had been promised never arrived.

Almost immediately, the second-guessing began.

Was Y2K a Real Threat or Mass Delusion?

Two stories quickly formed. First came the “crisis averted” argument: believers insisted disaster didn’t happen precisely because they worked so hard to stop it. John Koskinen, the Y2K czar, famously complained, “We’re victims of our own success,” meaning the smoother things went, the more suspicious people became. Senator Bob Bennett pointed to Pakistan’s market issues and sarcastically asked critics, “All right, would you want the New York Stock Exchange to go through this?”

But skeptics pushed back hard. Many pointed out that countries and companies that did next to nothing faced no greater problems than those that spent fortunes. Italy, Russia, and South Korea barely lifted a finger on Y2K; nothing terrible happened.

In 2004, economist John Quiggin bluntly said, “most of the money spent on Y2K compliance was wasted,” arguing the scale of the threat had been massively exaggerated. And the fact that many expensive Y2K programs were quickly canceled or shut down after January 1 seemed like a tacit acknowledgment that organizations knew they’d overreacted.

Ironically, the fixes themselves sometimes caused issues. A U.S. spy satellite system crashed on New Year’s Eve, not because of the dreaded bug, but due to a faulty patch meant to fix it.

Y2K Changed Technology Forever

Photo: Y2K Czar John Koskinen / CSPAN

Whatever you believe about Y2K, it left marks on technology and culture.

It taught programmers that yes, software sometimes outlives its expected lifespan. Modern systems now use four-digit years or more sophisticated date representations. Information technology went from a back-office function to a boardroom concern. And the crisis response created templates for future emergency management and international cooperation.

Culturally, Y2K became shorthand for feared catastrophes that fail to materialize—though whether that suggests wise preparation or needless panic depends entirely on your perspective.

Twenty-five years later, the evidence suggests Y2K was both somewhat overblown and a valuable exercise. The most apocalyptic scenarios were improbable, but the remediation efforts prevented numerous smaller disruptions that could have accumulated into significant problems.

Some will insist, “But nothing happened. Was it really worth it?” History tells us: “Yes. Because nothing happening was the goal.”